CITY FOOD MAGAZINE

http://www.cityfood.com/culture/art_%26_design/art_at_sustenance#focusPoint

Tuesday, October 13, 2009

SUSTENANCE FESTIVAL

Event catered by Bishop Winery

Event catered by Bishop WineryThe Sustenance, Feasting on Arts and Culture Festival kicked off on a cool Vancouver day in October. Artists, poets, musicians, and activists all gathered in the Roundhouse Community Center for an entertaining and informative evening of food security related activities. The Bishop winery catered the event with tray after tray of fabulous local concoctions, environmental organizations explained their achievements and future goals through various audio-visual displays, and artists spread out their wares for all to peruse and admire.

Cornacopia installation

Cornacopia installation The Maiz es Nuestra Vida Exhibit created by the MAMAZ collective played a major role on the festival. Artists Marietta Bernstorff, Laura Alvarez, Noel Chilton, Favianna Rodriquez, Adriana Calatayud, Cristina Luna, Mariana Gullco, Emilia Sandoval, Nadja Massun, Lucero Gonzáles, Julia Barco, Luna Marán and Ana Santos expressed their concern about Mexico’s corn situation through collage, photography, painting, and sculpture.

Noel Chilton was hand to give a brief speech (see below) about our objectives, to lead a workshop in metal corn ornaments, and to hand out flyers promoting the cause. Many visitors attended the opening and more will be streaming through as the festival continues in the Roundhouse exhibit hall with various events including an Erotic Food event and some Family Day activities. All the activities and exhibitions strive to motivate the public to eat locally, get active in supporting eco-friendly practices, and create art that pays homage to nature’s miracles.

Good evening. As you’ve just heard, I am here to represent our women artists cooperative MAMAZ ( Mujeres Artistas y el Maiz). Our objective is to raise consciousness in our community and abroad about the eminent danger that our corn crops are facing today. We express our concern about our native seeds through our art.

You may be thinking that I don’t look very native, and you’re right. My roots stretch back to Germany, England, and Poland. If I were a plant, I would be the mother of all hybrids. My children have even more mixed up traits. 11 years ago, I exported myself from the United States to Mexico. Unfortunately, my fellow countrymen, including representatives from Monsanto, beat me to it. I would like to think my arrival in Mexico was more benign. Obviously, I am not genetically altered or I would be 6’2” not 5’2” and my offspring would be perfect clones of myself. I think my boys are pretty swell, but they’re not perfect. Now, I am here in your beautiful country because this white girl doesn’t need a visa while my brown colleagues do.

It doesn’t make a lot of sense, but it’s a fact of modern day life. This is hard to swallow, but what is even harder to swallow is the invasion of genetically altered seeds from my original homeland to my adopted homeland. This is not only devastating for the farmers, but for the consumers and the population in general. The farmers get trapped in a vicious cycle of debt and dependency on foreign seeds, fertilizers and pesticides. The consumers get an expensive, unhealthy product, and the population starts losing its legends, traditions, and cultural identity, which are all centered on corn.

We women feel especially effected. The cobs of corn plant are the female organs. Its grains have nourished babies, children and adults for over 8000 years in Mesoamerica. We mothers must now think about how to feed future generations. We can stuff them with foreign foods, and their bellies will be full, but will their minds and their souls?

This is a question we mothers and fathers and caregivers of future generations have to ask ourselves not only in Mexico, but all over the world. What can we do to ensure a safe, healthy future for our loved ones?

We, as MAMAZ members, are attempting to go just that through our art. Thanks for your attention. I hope you enjoy the show.

Noel Chilton

Fotos: Stain Rice

Fotos: Stain Rice

Sustenance Festival, Vancouver, BC

Vancouver, BC – The Roundhouse, Get Local (a partnered project of FarmFolk/CityFolk and the Vancouver Farmers Market) and the BC Farmers’ Market Nutrition and Coupon Project are proud to present “SUSTENANCE: Feasting on Art & Culture.” A first time, unique celebration, SUSTENANCE Festival starts on Thursday, October 1 and culminates on World Food Day: October 16th. SUSTENANCE endeavours to connect the communities of art, culture, and food security. From global to local, from historic to present day, the art and culture of food will be something everyone can feast on.

SUSTENANCE Festival kicks off with the opening celebration on Saturday, October 3, a party for all of the exhibitors and producers who are participating in SUSTENANCE Festival, special guests and the public. Guests can enjoy local food and Lotusland Wines while perusing the exhibits, including internationally acclaimed El Maiz Es Nuestra Vida (“The Corn is Our Life”), a contemporary art exhibition from Oaxaca, Mexico that guides the public through the history of corn throughout the Americas, and CORNUCOPIA, an interactive installation designed to bring an understanding to the average citizen of the great environmental stress and energy consequence of industrializing our food. The night will feature live music, presentations, and a chance to be amongst the first to explore the many exhibits of SUSTENANCE Festival.

For a full list of SUSTENANCE Festival exhibits and events please check out SUSTENANCE FESTIVAL.

VIDEO : "Corn is Our Life / Miaz es Nuestra Vida"

Realizado por: Luna Marán, Julia Barco, Nadia Massún, Marietta Bernstorff y Lucero Gonzalez.

DIRECTIVE COMITTEE

In order to improve the productivity of the group, we have decided to create an executive committee. This committee may evolve and change in the same way the collective does. Anyone who wishes to participate can do so when they choose. It also permitted to leave the committee if necessary. We need a minimum of 5 artist members in order to make any pertinent decisions.

In Mexico City:

Adriana Calatayud, Selma Guisanse, Ana Gomez

In Oaxaca:

Emilia Sanoval, Edith Morales, Noel Chilton, Marietta Bernstorff, Mariana Gullco

We still need someone to take responsibility for the Bolsa del Mercado bag.

If you are interested, please contact Marietta.

In Mexico City:

Adriana Calatayud, Selma Guisanse, Ana Gomez

In Oaxaca:

Emilia Sanoval, Edith Morales, Noel Chilton, Marietta Bernstorff, Mariana Gullco

We still need someone to take responsibility for the Bolsa del Mercado bag.

If you are interested, please contact Marietta.

Centro de la raza, San Diego 2009

"In the southern part of Mexico, women spend their whole day preparing fresh masa (corn dough) for the biggest and thinnest tortillas. The video pays homage to their life-sustaining practice and to the texture of life itself, threatened by the introduction of genetically modified corn, which can destroy the variety of corn that has been produced naturally for thousands of years."

Julia Barco

"In the Popol Vuh, the sacred book of the Quiche Maya, man is originally made out of corn.

This video suggests a human being transformed into a Barbie, or a genetically modified corn."

Gitte Daehlin

"The Monsanto House of the Future was created by Monsanto's plastics division. It existed at Disneyland, CA from 1957-1967. It was mostly made of plastic and featured ideas like a dishwasher that used microwaves instead of water. Legend has it that instead of one day, it took two weeks to demolish it because the wrecking ball would just bounce off it. DAS finds it the perfect spot to "sweep" into action by perhaps burying the house in GM corn."

Laura Alvarez

"In January 2007, the Mexican government approved an increase in the price of corn, staple of the Mexican diet. This irresponsible act placed millions of Mexicans who live in extreme poverty at the edge of starvation. Furthermore, the government allowed the introduction of genetically modified corn; this creates a risk to the endemic varieties of corn.

Higher and Lower, serves as an analogy, as the prices of tortillas keep going up, our standard of living goes down."

Luna Marán

Since Party for National Action (PAN) came into power in Mexico, the price of basic food staples has risen, coinciding with an influx of genetically modified corn. This piece (which was originally a poster and is now intended to be applied on a wall) is a play on words since "pan" means bread. It refers to the paradox of the rise in tortilla prices (and inability of the people to get used to bread) and the current governing political party (PAN).

Ana Santos

CUBA Biennal 2009

Centro de Arte Contemporáneo Wilfredo Lam,

27/03/2009 - 30/04/2009

La Habana Vieja, Cuba

10th Biannual Exhibit- Havanna

“Integration and Resistence in the Global Age”

In 2007, Ibil Hernandez Abascal, one the Bienal’s curators, visited Oaxaca and became familiar with the “Maize is Our Life” project. The project comprises various languages and arguments. It strives to educate the consumer, or simply raise awareness, about this crop, which in realty is our CULTURE and an essential part of our identity. Touched by these voices of protest, Ibil Hernandez decided to include the project en the subsequent “Bienal.”

Marietta Bernstorff curated the “Maize if Our Life” exhibit, which was transported to and exhibited in the Regional Fine Art and Design Center—an old, two-story building with plenty of personality. The exhibit reunited approximately 25 artists who contributed pieces in various media, including: photography, video, installation, shadow puppets, and posters. Marietta Bernstorff opened the show with an introduction to the project and a tamale feast, which quickly evolved into a “fiesta” with music, mezcal, and plenty of corn.

The show received favorable reviews and was visited by hundreds of people. Of all the participating projects, the “Maize is Our Life” exhibit was one that best represented the premise of the “Bienal.”

The exhibit converges but doesn’t fuse. It respects every kind of origin and context, unifying various voices in one shout that cannot be silence. It defends the clear victim of globalization. I am not referring solely to the crop as a food staple, but also as an identity—the identity of a people whose history stretches back millions of years.

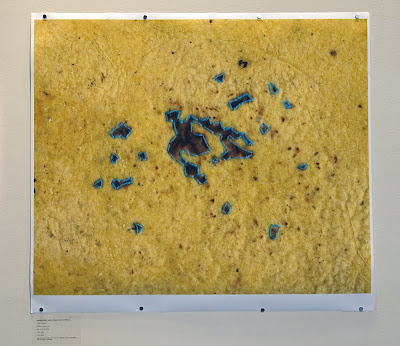

Jessica Segall, 2009

Jessica Segall, 2009

The “Market Bag” project accompanied the “Maize is Our Life” exhibit. It included over 95 objects, developed by artists and craftsmen from Mexico and Cuba.

On March 20th, Marietta Bernstorff led a workshop entitled “A Meeting of Cultures,” in which 25 Cuban women participated. During the workshop, there was much discussion of the origin of maize, the difference between native seeds and genetically altered ones and the taste difference between natural foods and their rival. The objective was to “Return to the memory of our cultures.”

During the workshop, and after having covered the theoretical framework, the group was decided in two parts. Half worked with native corn and the other half with genetically altered corn. Using the results of this activity, a collage was made to be placed at the exhibit’s entrance as a symbol of our solidarity with the Cuban women.

Martha Toledo, 2009

Martha Toledo, 2009

Adriana Calatayud, 2009

Adriana Calatayud, 2009

Juane Quick to See Smith, 2009

Juane Quick to See Smith, 2009

Juane Quick to See Smith, 2009

Juane Quick to See Smith, 2009

Opening, Havanna 2009

Opening, Havanna 2009

Invited artists (Mexico, the United States, and Cuba), curated by Marietta Bernstorff:

Selma Guisande

Emilia Sandoval

Adriana Calatayud

Mariana Gullco

Gitte Daelin

Lorena Silva

Martha Toledo

Ana Santos

Sara Corenstein Woldenberg

Mari Olguín

Juane Quick to See Smith

Jessica Segall

Jacqueline Brito

Hilda María Rodríguez

Judy Baca

Video Group:

Luna Marán

Julia Barco

Nadia Massun

Marietta Bernstorff

Lucero González

Group Advertencia Lírika: Rap

Ixchel Alejandra López Jiménez

Marlene Cruz Ramírez

La Piztola (Stencil group from Oaxaca)

(Rosario Martínez Llaguno, Roberto Vega Jiménez, Yankel Balderas Pacheco)

Market Bag: 95 products made by women artists

10th Biannual Exhibit- Havanna

“Integration and Resistence in the Global Age”

In 2007, Ibil Hernandez Abascal, one the Bienal’s curators, visited Oaxaca and became familiar with the “Maize is Our Life” project. The project comprises various languages and arguments. It strives to educate the consumer, or simply raise awareness, about this crop, which in realty is our CULTURE and an essential part of our identity. Touched by these voices of protest, Ibil Hernandez decided to include the project en the subsequent “Bienal.”

Marietta Bernstorff curated the “Maize if Our Life” exhibit, which was transported to and exhibited in the Regional Fine Art and Design Center—an old, two-story building with plenty of personality. The exhibit reunited approximately 25 artists who contributed pieces in various media, including: photography, video, installation, shadow puppets, and posters. Marietta Bernstorff opened the show with an introduction to the project and a tamale feast, which quickly evolved into a “fiesta” with music, mezcal, and plenty of corn.

The show received favorable reviews and was visited by hundreds of people. Of all the participating projects, the “Maize is Our Life” exhibit was one that best represented the premise of the “Bienal.”

The exhibit converges but doesn’t fuse. It respects every kind of origin and context, unifying various voices in one shout that cannot be silence. It defends the clear victim of globalization. I am not referring solely to the crop as a food staple, but also as an identity—the identity of a people whose history stretches back millions of years.

Jessica Segall, 2009

Jessica Segall, 2009The “Market Bag” project accompanied the “Maize is Our Life” exhibit. It included over 95 objects, developed by artists and craftsmen from Mexico and Cuba.

On March 20th, Marietta Bernstorff led a workshop entitled “A Meeting of Cultures,” in which 25 Cuban women participated. During the workshop, there was much discussion of the origin of maize, the difference between native seeds and genetically altered ones and the taste difference between natural foods and their rival. The objective was to “Return to the memory of our cultures.”

During the workshop, and after having covered the theoretical framework, the group was decided in two parts. Half worked with native corn and the other half with genetically altered corn. Using the results of this activity, a collage was made to be placed at the exhibit’s entrance as a symbol of our solidarity with the Cuban women.

Martha Toledo, 2009

Martha Toledo, 2009 Adriana Calatayud, 2009

Adriana Calatayud, 2009 Juane Quick to See Smith, 2009

Juane Quick to See Smith, 2009 Juane Quick to See Smith, 2009

Juane Quick to See Smith, 2009 Opening, Havanna 2009

Opening, Havanna 2009Invited artists (Mexico, the United States, and Cuba), curated by Marietta Bernstorff:

Selma Guisande

Emilia Sandoval

Adriana Calatayud

Mariana Gullco

Gitte Daelin

Lorena Silva

Martha Toledo

Ana Santos

Sara Corenstein Woldenberg

Mari Olguín

Juane Quick to See Smith

Jessica Segall

Jacqueline Brito

Hilda María Rodríguez

Judy Baca

Video Group:

Luna Marán

Julia Barco

Nadia Massun

Marietta Bernstorff

Lucero González

Group Advertencia Lírika: Rap

Ixchel Alejandra López Jiménez

Marlene Cruz Ramírez

La Piztola (Stencil group from Oaxaca)

(Rosario Martínez Llaguno, Roberto Vega Jiménez, Yankel Balderas Pacheco)

Market Bag: 95 products made by women artists

PAR A PAR, Mexico City 2008

MAMAZ COLLECTIVE SHOW

November 2008 / Manuel Felguérez / Multimedia Centre CNA / México City

Ana Gómez, 2008

Ana Gómez, 2008

Emilia Sandoval, 2008

Emilia Sandoval, 2008

Sara Corestein, 2008

Sara Corestein, 2008

November 2008 / Manuel Felguérez / Multimedia Centre CNA / México City

Ana Gómez, 2008

Ana Gómez, 2008The Par-A-Par Festival took place in Mexico City in November 2008 with the objective of promoting exchanges between artists, scientists and activists. In other words, it strove to create a creative dialogue and a set of agreements based on the analysis and production of projects with real applications in social spheres.

During seven days, people from different backgrounds and experience levels came together to germinate projects that contemplated the creative use of technology to create public spaces for critical discussion.

During seven days, people from different backgrounds and experience levels came together to germinate projects that contemplated the creative use of technology to create public spaces for critical discussion.

Emilia Sandoval, 2008

Emilia Sandoval, 2008The MAMAZ collective has a peaceful resistance project focused on promoting social critique in order to raise consciousness about the problems that corn and food in general face today. This project fit with the objective of the festival and so, we participated with our El MAIZ ES NUESTRA VIDA/ CORN IS OUR LIFE exhibition.

Sara Corestein, 2008

Sara Corestein, 2008The MAMAZ collective expresses its freedom of speech in the art field. We consider active participation a necessity. Thus, we have gathered women—artists, craftswomen, and creative people in general—interested in speaking about the theme of nutrition and corn through their own form of action. Ten of the collective’s artists, using different media, spoke of the history, the myth, the nutritional importance, the modification of genetics, and the rising price of corn.

In conjunction with the show, discussions were held about the use of accessible resources to spread the news about the project.

In conjunction with the show, discussions were held about the use of accessible resources to spread the news about the project.

Market Bag

Casa Lamm, 2008

Casa Lamm, 2008The Market Bag, which complements the “Maize is Our Life” project, is an additional itinerant exhibit of art-objects. Other women artists residing in the area in which the exhibit is being hosted by a cultural institution Women from the collective are joined by other women artists residing in the area in which the exhibit is being hosted by a cultural institution. The institution holds workshops, which invite and integrate these women into the project. The two-day workshop includes some of the original artists, guest curators, and other invited locals who are working in this subject matter. At the end, the participants create two pieces for the market bag.

The first day, the women participants view a brief DVD about the history of corn. They discuss the difference between native seeds and genetically altered ones, the situation in which native seeds find themselves around the world, and ultimately the flavor of food made with native corn which brings us back to our cultural memory. This is the most important reason for keeping the seeds and our memory alive. During the second day, the women begin creating a piece while they examine other pieces already in the exhibit. They also observe other related pieces that have been exhibited in other shows as examples of what kind of artwork can be considered for the Market Bag exhibit.

These workshops are free of cost to interested women. They are given in the cities in which the exhibit is being shown, allowing the art-object exhibit to grow and raising consciousness of the global predicament. The women work with the same concept as that which inspired the “Maize is Our Life” exhibit. The themes are directly related to corn, the seeds and cultural memory. The women generally have some craft experience. They range in age and represent various cultures, economic status, and social levels

As the women create their objects, they tell their story about what corn as a symbol of globalization and worldwide strife means to them. These stories are documented for the following show, which serve to give future women an idea about what other women think about corn and what they are doing to save native seeds and their cultural memory. This project was exhibited in Casa Lamm in Mexico City and in the Santo Domingo Museum in San Cristobal, Chiapas in 2008.

Green Corner, Mexico City. 2008

Green Corner, Mexico City. 2008Special thanks to Armando and Gabriela, from Itanoní restaurant, Oaxaca

Green Corner, Mexico City. 2008

Green Corner, Mexico City. 2008Special thanks to Armando and Gabriela, from Itanoní restaurant, Oaxaca

Mamaz Collective

The “Maize is Our Life” exhibit closure in the Natural History Museum, in which 48 women joined forces and creativity in a pro-corn movement. Here, taking advantage of the inertia, the collective concept was born.

MAMAZ begins and develops at the beginning of 2008. It is an open group in which the only requirement is to raise consciousness. MAMAZ, beyond participating in new exhibitions and promoting the original :Maize is Our Life” exhibit, has generated parallel projects in order to reach a wider public.

The Market Bag, for example, was also born in 2008. It is an art-object project in which almost 150 women artists, artisans, farmers, and housewives are participating and telling their stories about corn.

mamazmarketbag.pbworks.com

mamazmarketbag.pbworks.com

The collective also organizes workshops to be given in villages or in exchange with other womens’ groups. In these cases, discussions about the corn situation and how to raise consciousness are debated. Participants are also invited to create something for the bag. The idea is to bring people closer to corn not only through theory, but by picking up on what they feel for it and figuring out how to express this three-dimensionally.

The Market Bag and the blog focus on social action and artistic expression. Marietta Bernstorff never tires of visiting villages and festivals promoting the conservation of native corn and our nutritional independence.

Natural History Museum, Mexico City 2007

Germaine Gómez Haro

El maíz es nuestra vida / Corn is our life

In our country, the relationship between man and corn dates back to the dawn of Mesoamerican civilization and travels far beyond the mere nutritional factor. Corn cultivation determined economic, political and social devellopement in ancient Mexico. Hence, it is considered the “primordial plant”—the sustenace of the people who gave credit to one of the most important gods in the precolumbian world. Those in the Aztec world called her Centeotl, and in her masculine state-Chicomecoatl. She was patroness of terrestrial fertility. Xilonen is the name given to the tender corncobs, while Ilmatecuhtli represents the old, dry cobs. Among the Zapotecs, the patron of corn is Pitao Cozobi, and according to Popul Vuh legends, the gods created man from cornmeal. Innumerable works of art relay the importance of the corn cult in the Mesoamerican society. The indigenous people have conserved and perpetuated these traditions throughout the centuries, which form the most intrinsic foundations of our identity today as Mexicans.

“Maize is our life,” proclaim 48 artists native to or residents of Oaxaca. They speak by exhibiting their forms of expression in the exhibit entitled with the same phrase. It was present in the Natural History Museum until February of 2009.

Concern about the dangers that genetically altered crops impose the survival of native corn led this group of artists to create an exhibit which would eventually include painting, sculpture, prints, installation, art-object, photography, and video. Artists and founding members of the Curtiduria (an alternative art space dedicated to the exhibition of and the promotion of, contemporary art in Oaxaca), Demian Flores and Marietta Bernstorff, launched a call for entries for women wishing to create artwork based on the corn theme. More than one hundred entries pored in. The show exhibited a selection of fifty-two pieces of various media with the intention of expanding the show and altering it to include new participants. Another motive of this singular exhibit was to reunite well-known artists, blossoming artists, and social activists in order to form a common voice that would protest the blindness and the obstinacy of those who support transnational corporations that are contaminating the Mexican farmland with their diabolic genetically-altered seeds for the economic benefit of a handful of people. The irreversible health damage that these altered crops pose is also grave. It is imperative that we raise awareness in the Mexican people of the severity of the problems caused by the loss of our ancient traditions and values, which have given our now endangered culture its extraordinary richness.

Juanita Vasquez, Zapotec social activist and community leader from Yalalag, was present at the opening. She has been instrumental in defending native corn in Oaxaca. She advised many of the women who participated in the show about the fundamental role that corn plays in the daily life of the indigenous people. “We are digging a grave here in our country,’ exclaimed Juanita, “We are burying our culture. No matter the cost, we have to save the corn that it our sacred inheritance.”

Among the various exhibited works, the artists expressed their very personal interpretations on the importance of corn and its close ties to indigenous women and the land. It can be considered a sacred plant. The vocabulary and techniques employed were numerous. The genius and the audacity in which this critical theme was expressed were noteworthy. Such is Izmalli Coca’s case. She contributed the piece entitled “Esteril o Fructifera (Sterile or Fruitful),” which recreated the history of Sara, a mannequin representing Mother Earth, dressed in a gown made with pieces of tortilla and corn grains.

The “Maize is Our Life” theme poses an interesting reflection based on humor, irony, and artistic beauty, as poet Natalia Toledo puts it. “Scatter purple grains across your petate in order to learn about the cob from which you are made. Thresh your body on the comal and its fire. On this earth, we are grains of corn.”

La Jornada, Sunday October 14th, 2007

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)